Traditionally, tiny models of human tissue that mimic human physiology, known as microfluidics, organ-on-chip, or microphysiologic systems, have been made using synthetic materials such as silicone rubber or plastics, because that was the only way researchers could build these devices. Because these materials aren’t native to the body, they cannot fully recreate normal biology, limiting their use and application.

Collagen is well-known as an important component of our skin, but its impact is much greater, as it is the most abundant protein in the body, providing structure and support to nearly all tissues and organs.

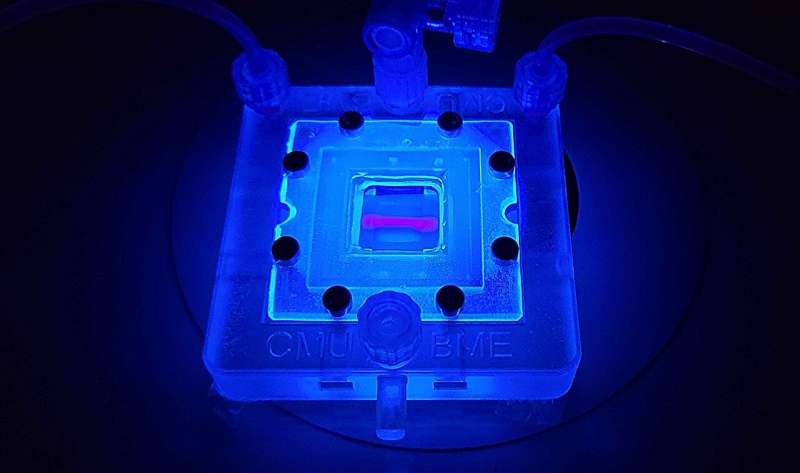

“Now, we can build microfluidic systems in the Petri dish entirely out of collagen, cells, and other proteins, with unprecedented structural resolution and fidelity,” explained Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering and materials science & engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. “Most importantly, these models are fully biologic, which means cells function better.”