Damage to the CFC tissue—common in sport-related injuries—does not mend well. To improve healing treatments, scientists need to better understand the structure of this tissue and how it reacts to varying types of pressure.

How the tissue responds to stress

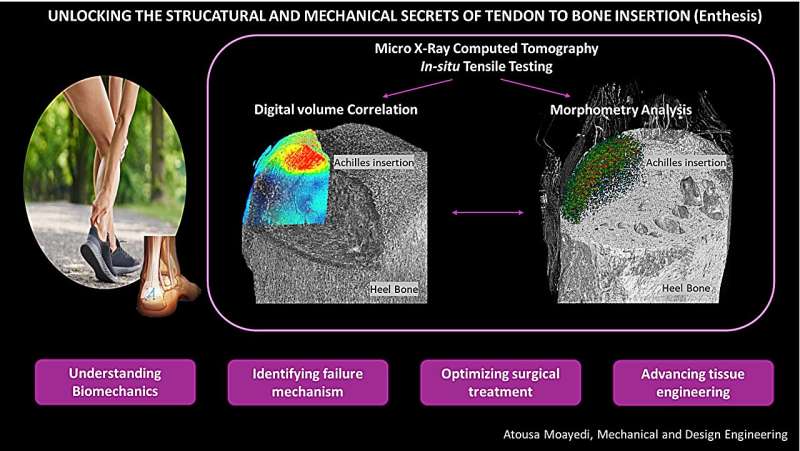

Research by Atousa Moayedi, a Ph.D. student in the University of Portsmouth’s School of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering, has been able to demonstrate that the center of the CFC tissue changes shape more than the surrounding areas, when stressed at different angles.

In areas where the microscopic cavities within the tissue (the lacunae) were more densely packed, the distortion was greater. This means that the way the tissue layers are arranged, and how thick they are, strongly influences how stretching (strain) is dispersed where the tendon meets the bone.