In the first paper, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, scientists developed a targeted cell therapy against pemphigus vulgaris (PV). This severe autoimmune skin disease causes blisters and sores.

They took the cells that were causing the disease (Dsg3-specific pathogenic T cells) from mouse models and human patients and converted them into harmless Treg cells. They used specialized chemical tools to switch on a gene called Foxp3, which controls a cell’s ability to help the immune system, and cut off a specific activation signal to prevent the cells from turning back into attackers.

No more broad suppression?

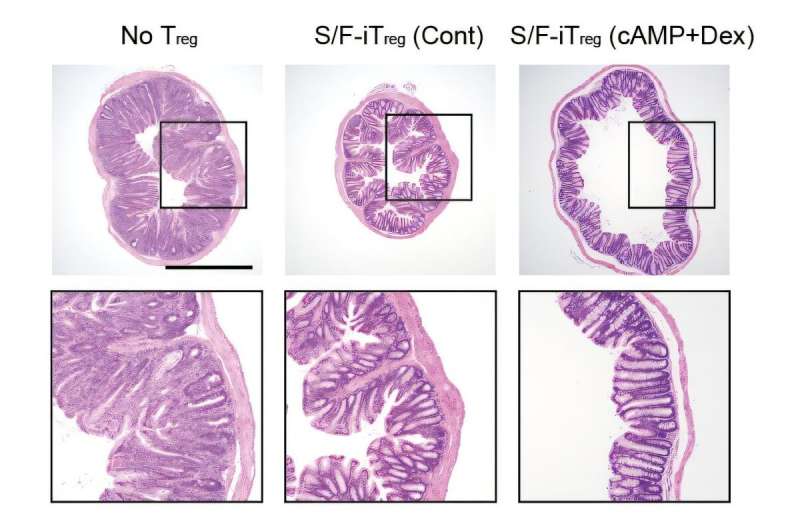

To demonstrate that the technology works, the researchers injected newly generated Treg cells into a mouse model of PV. These modified cells migrated directly to the affected immune areas (skin-draining lymph nodes), selectively shutting down the autoimmune attack and reducing blistering without suppressing other parts of the immune system. This targeted action is an improvement over traditional immunosuppressant drugs, which can weaken the immune system as a whole.