But this approach has its limits. Although it provides good intuitive depth perception, it doesn’t allow surgeons—or surgical robots—to extract precise measurements from what they see.

Estimating exact distances or shapes using just two images is difficult, especially in complex surgical environments where lighting is uneven, surfaces reflect harshly, and tools may block the view. These challenges have slowed progress in surgical automation and real-time feedback tools.

Preoperative 3D scans, like MRIs or CTs, can help, but they don’t update during surgery as tissues shift or change. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) offers detailed real-time data, but it covers a small area and produces black-and-white images that can be hard to interpret.

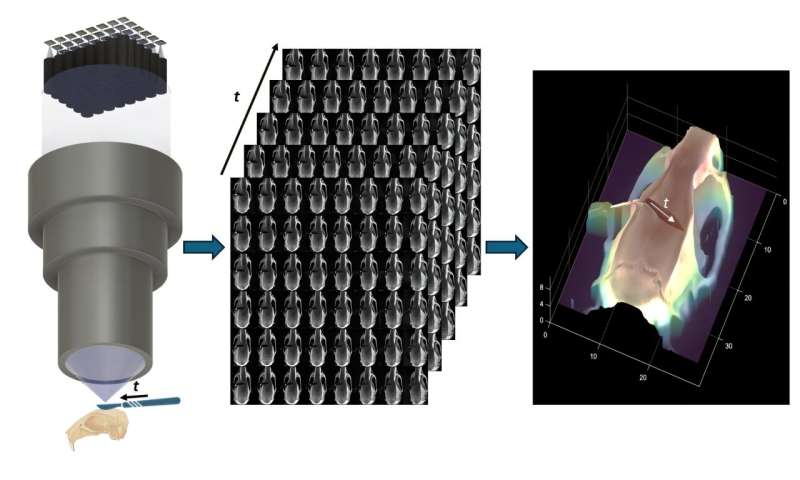

To meet the need for better 3D imaging that works during live surgery, researchers recently developed a new kind of surgical microscope called the Fourier lightfield multiview stereoscope, known as “FiLM-Scope.” Their report is published in Advanced Photonics Nexus.